Amid the pandemic, women bear the burden of ‘invisible work’

PHOTOS AND TEXT BY

Bernice Beltran

When she was living with her ex-partner, Amy (not her real name) spent most of the day doing chores and taking care of her children. Then she would go to the fish port in the evening and work until 3 a.m.

“My ex rarely helped out in the chores,” Amy said. To make matters worse, her alcoholic husband beat her up almost every week.

Breaking up with her abusive husband was easier said than done. “Where will I go? Who will look after my children when I go to work?” Amy asked.

According to Oxfam International, chores like cleaning and cooking, as well as looking after children and elders, are crucial to “human and social well-being.” Yet the responsibility often falls disproportionately on women and girls.

“In the Philippines, Oxfam’s assessment shows that women [were] twice as much more likely to carry the burden of household tasks, even before the pandemic,” said Leah Payud, Oxfam Pilipinas resilience portfolio manager.

Unpaid care work has prevented many women and children from pursuing education and career opportunities, trapping them in a cycle of poverty.

Juggling chores, caregiving, and work kept Amy from attending to her own needs. She wanted to work as a masseuse but could not find the time to enroll in a short course.

Last year, on the first night of the government-imposed lockdown, Amy’s husband was locked in jail after stabbing her while she prepared dinner. As her toxic relationship with her husband ended, Amy faced a new ordeal.

She now has to raise three sons by herself in a small tent in Smokey Mountain, a former dumpsite in Tondo, Manila.

Amy was also among the millions of Filipinos who lost their jobs during the pandemic.

She lined up for food donations and walked to nearby wet markets to convince vendors to hire her, but no one would.

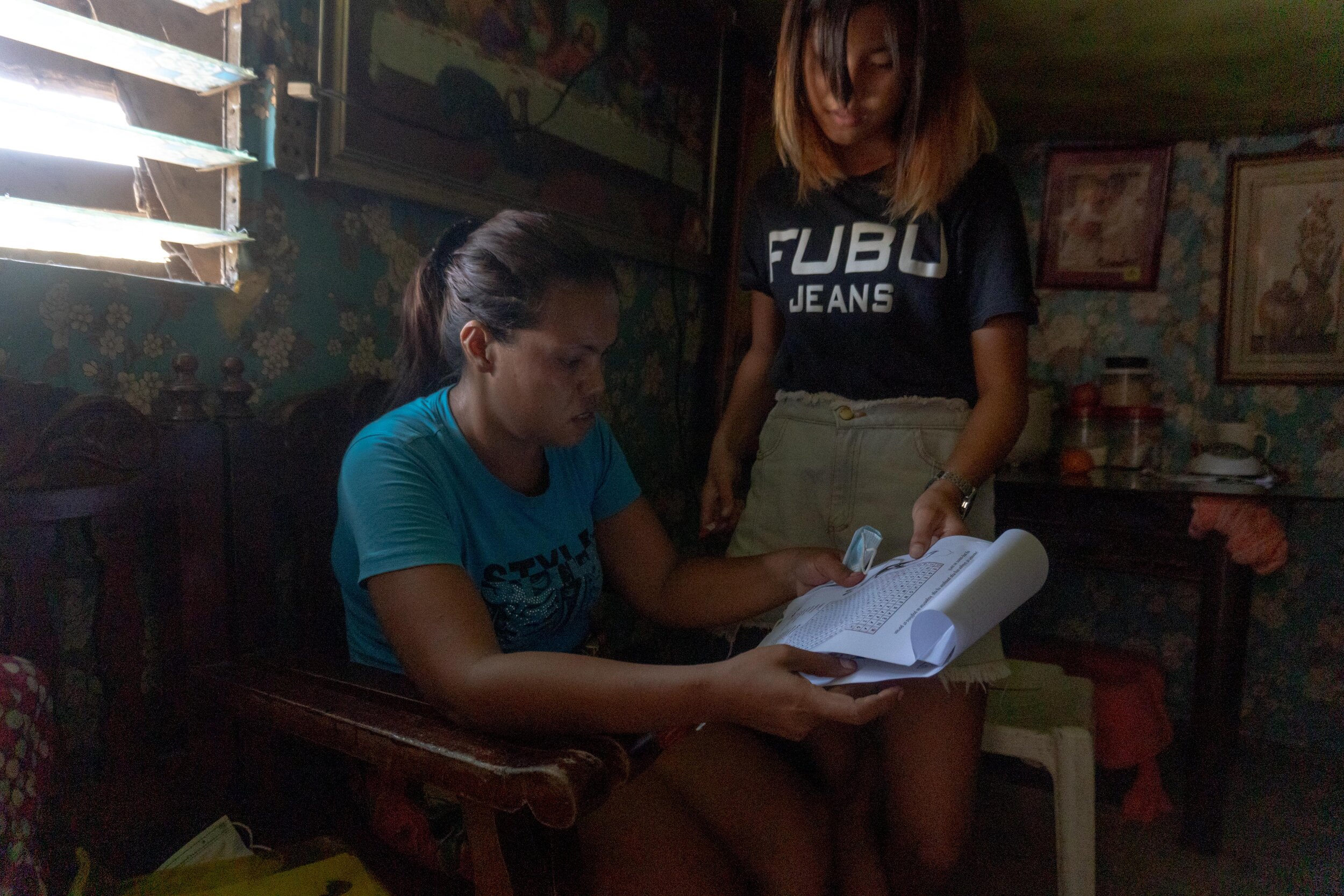

After learning about her situation, Amy’s pastor raised the idea of sending her children to the church’s foster care program accredited by the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). The pastor assured her that she could reunite with her children once she found a job.

“It was a tough decision to make,” Amy admitted. “I wanted to be with my sons but I couldn’t afford the life that they deserve.”

Increased Burden

Amid the pandemic, time spent on household work for both men and women increased, according to COVID-19 Rapid Gender Assessment (RGA) conducted by several NGOs and civil society groups led by Oxfam, as well as the United Nations. However, women still shouldered the bulk of the housework.

“The pandemic exacerbates the care work burdens carried by solo parents, women from indigenous groups, and those enrolled in the government’s social protection program,” Payud said.

“Care work should be everyone’s responsibility. Men contributing more to household chores and care tasks should be sustained as we create a ‘better normal’ within a just society,” she added.

Like Amy, Lucila Buladaco depended on government financial assistance and food rations during the strict lockdowns. She and her husband lost their jobs during the first few months of the pandemic.

Due to her heart condition, Lucila was advised by the doctor to refrain from strenuous activities. Her husband, son, nephew, and nieces took turns in doing housework.

Lucila realized a long time ago that she could not simply rely on one “breadwinner.” She was in fifth grade when her father passed away. Her mother, who was a housewife throughout her married life, struggled to find a job.

“I had to drop out of school and work as a house helper so I could send money to my family,” Lucila said.

She wanted to go back to school but never got the chance when her mother died a few years later.

Breaking the cycle

As the government began to ease the lockdowns last year, Lucila and her neighbor pooled in their resources to put up a food stall.

“We try to save money so we can survive the months where we can’t open our food stall because of the lockdown,” Lucila says.

Lucila also sets aside some money so her son, nephew, and nieces can go back to school when the pandemic is over.

“I want them to be able to stand on their own,” Lucila said.

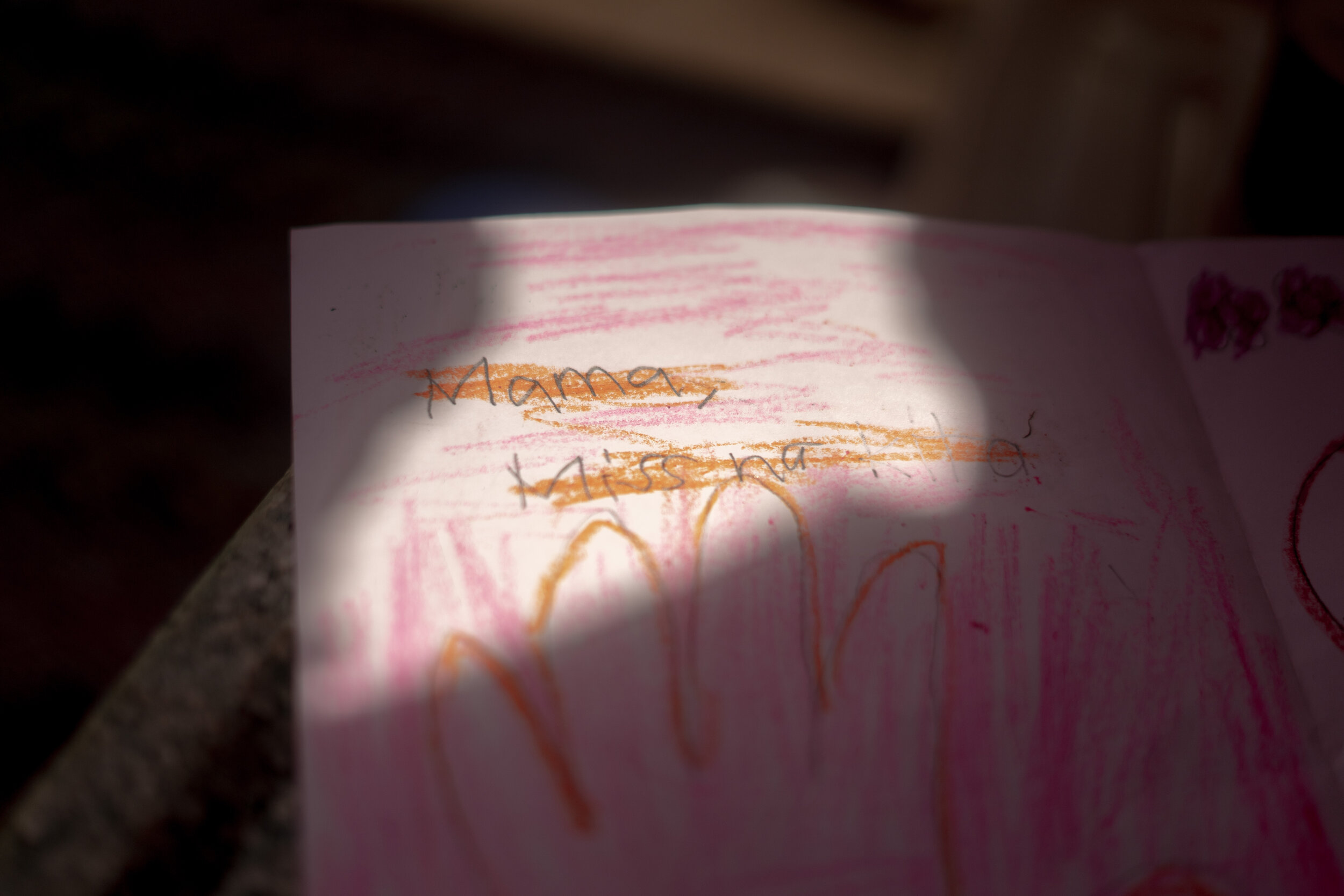

Amy agreed to send her children to foster care.

“The church provides my children with food, clothes, and education,” she said. “I’m happy that my sons can finally read, write, and speak in English. They even talk to me in English when we speak through video calls.”

Still, Amy misses her sons every single day.

This story is one of twelve photo essays produced during the Capturing Human Rights fellowship, a seminar and mentoring program jointly undertaken by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Photojournalists' Center of the Philippines.